I sometimes think that it can be difficult for this white Midwestern boy to truly comprehend racism and discrimination, both because I haven’t experienced it personally and because it is so foreign to how I was raised. It is almost otherworldly to me that a person would be persecuted simply because of who they…are.

Though I grew up in racially-divided St. Louis, I always thought my birth city made me far more racially accepting. I was a jazz musician and hung around smoky clubs, clinging to the advice of old black jazz musicians as though it were gold. Many of my music heroes were black. There were so many different types of people walking around that I just didn’t pay attention to skin pigment: they’re all just people.

I also came from a very spiritual family. The idea that you’d judge someone based on his physical body seemed so materialistic—so debased. Whether man or woman, black or white, what did this have to intelligence, compassion, integrity?

Duke Ellington was my favorite composer (well, and George Gershwin—a Jew). They were geniuses—my heroes. Hendrix changed rock and roll. Miles revolutionized jazz. Elvin Jones was one of my favorite drummers. I listened to him over and over again. They were amazing, truly great…and I loved them. Mom took me to see B.B. King at the Fox Theater when I was still a kid because she wanted me to see him while he was still alive…to see a living legend. I remember the floor shook as I stood by one of the house speakers, riveted. King didn’t play guitar. He sang through it. He spoke. He told stories. Lucille, the name given to his guitars, didn’t seem like an instrument so much as an extension of him. His band was tight; his drummer, killer. To me they transcended the human condition, capturing just a bit of the divine called greatness, having honed their craft for years to the point where they seemed more than mere mortals.

_______________

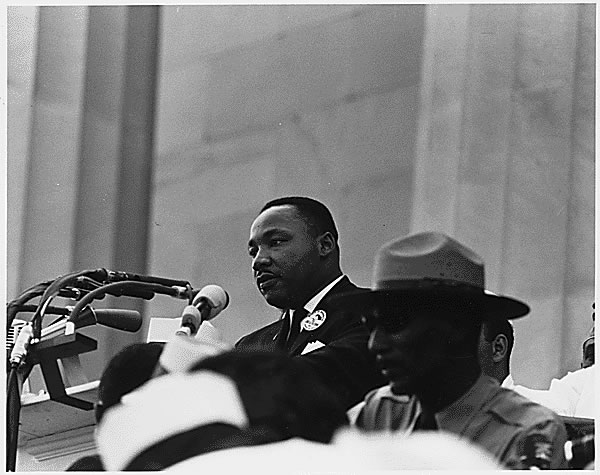

Today I was reminded it was Martin Luther King, Jr. Day.

I experienced a bit of unanticipated emotion as I glanced at his name. I had forgotten the day was approaching and wasn’t thinking about it, nor had it even been on my radar. I had just caught up with some deadlines and was about to get to work. And then there it was: Martin Luther King. I got almost choked up for a second: Thank you, Dr. King.

As I write this in a racially-integrated part of St. Louis, a white person who has never experienced racial discrimination, it could seem odd for me to be thankful for Dr. King. His work never impacted me. He never provided freedom for me. He never changed my life.

But, au contraire, he in fact did. Dr. King changed everything.

You see, I’m an American. Like it or not, that’s where I was born and that’s what I am. Long ago there was a great evil in this country, an evil that has existed across the world back to the time of the Greek helots and before: slavery.

Slavery was a stain on the brilliant flag of personal liberty flying over American soil since the Revolution. Though formally abolished in 1865, its stench continued to hang over the United States in the form of discrimination and segregation which continued into the 1960s. Not outright captivity but not freedom, segregation was a covert form of bondage—the ability to restrict the life of another simply because of who he was. It rankled the soul and hypocritically stood in stark contrast to the basic tenets on which America was founded.

The idea that you can own another human being is insane, yet amazingly has been widely accepted by whole populations at different points in history. Slavery is, at its root, tyrannical—as are all forms of oppression. The serfs of Russia, the feudal peasants of medieval Europe, the coolies of China or the Untouchables of India were all denied full standing as human beings simply due to the nature of their birth. They did nothing wrong; they hurt no one. Yet, because of who they were, they weren’t valid.

This is injustice.

Often very legal, these systems were brilliantly justified and defended by the “great thinkers” of their times. They were supported by whole populations. And while it is easy to speak about their wrongness in retrospect, sitting in a more “civilized” age, those systems were so widely agreed upon at the time that those who dared disagree did so only at their very real peril.

Speakers of freedom threatened the status quo. They endangered someone’s power and, as such, were paid with imprisonment, torture and execution for their writings and speeches.

Throughout history these people stood as defiant giants above a field of reprehensible permissiveness, clearly stating the truth when others would only mumble in fear. They held their own ideals even when society around them cravenly agreed or even supported the oppression they knew in their hearts was wrong.

It is an amazing thing, the power of threats, in changing a man’s mind. One has one’s ideals up to the point where it might be uncomfortable. When the potential pain of adhering to principle becomes too great, it is amazing how thoroughly one can change one’s mind about right and wrong.

Imprisonment, death, torture, threats on one’s family—these are all powerful motivators. And the elasticity of a mind under threat is incredible, allowing even the most illogical ideas to suddenly seem very rational indeed—they better be, or else one has a real problem: they would have to do something about it.

Yet in spite of all of that, for millennia certain people did disagree. They stood up and made it their problem personally; they made it their life’s work. They involved their families and their friends. They had little kids and jobs too, but they didn’t just watch it or read the newspapers. It had to do with them—it wasn’t “over there” or a “social issue”—it was their life.

They were that giant kind of human being in possession of such an infinite well of determination, uncompromising dignity and profound personal sense of justice that they stood against all odds to make a change. Mahatma Gandhi, Patrick Henry, Nelson Mandela and countless others—they were speakers of truth; speakers of freedom.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was born in a time period where it was perfectly acceptable to oppress people based on race—even in a country whose basic ideals included freedom and personal liberty. It was a time where racially-motivated crimes such as lynchings were commonplace. Government laws institutionalized discrimination—laws enforced by rifles, tear gas and clubs. Officially sanctioned by the state and emphasized by insane bigots and bullies, oppression of American citizens based on race wasn’t just prevalent—it was legal.

Underscoring the deep agreement with these principles was the fact that the United States Justice Department, through the FBI, was even found to be using its vast powers to suppress anyone brave enough to change it.

Through illegal wiretapping, smear campaigns, blackmail, false media reports and even violence, they sought to “expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit or otherwise neutralize” the activities of the Civil Rights movement and its leaders.

The FBI agent assigned to King wrote, “In the light of King’s powerful demagogic speech…. We must mark him now, if we have not done so before, as the most dangerous Negro of the future in this nation from the standpoint of communism, the Negro and national security.”

Yet, Dr. King did not bow.

He marched in Washington. He marched in the Deep South. He spoke. He wrote. He inspired. He would not stop. He would not be silenced.

He used only non-violent means, saying “I refuse to accept the view that mankind is so tragically bound to the starless midnight of racism and war that the bright daybreak of peace and brotherhood can never become a reality…. I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word.”

When his own house was bombed, with his wife and baby inside—thankfully unhurt, he didn’t seek retribution. Instead, he spoke of peace and love to the armed crowd outside his house demanding revenge. When he received death threats he responded with reason.

Think of it! How would I respond? I have a daughter. What would I do?

He spread his dream to millions. He inspired a nation to be better than it was—and to do it without hatred, without violence and without retribution.

He firmly spoke the truth, holding to principle as a rock in a wave-tossed sea of violence and irrationality. He had the clear-eyed vision not to just protest injustice, but to protest solely with the truth. He urged people not to fight but to love, not to attack but to stand firm.

And so, as I listened to Hendrix as a teenager, I didn’t see the color of his skin; I just heard the tone of his guitar. When I listened to Miles, I didn’t think about how he was a “Negro”; I thought about how he was a genius.

The America I grew up in, only a few generations later, has been radically transformed. People are people—period. It never dawned on me to think anything else. This man changed my nation, and he did it with principles, ideals and truth alone.

So thank you, Dr. King.

Thank you for setting an example of freedom. Thank you for standing up and speaking out despite the very real consequences for doing so.

I’m sorry for your loss. I’m sorry for those consequences.

But I am thankful you existed. And this Martin Luther King Day I’m thankful for the reminder…a reminder of who I want to be and that this is defined by the choices I will make.